What Higher Ed Can Learn From the Newspaper Industry – The Chronicle of Higher Education

February 25, 2019

Presidents skeptical that some colleges closing can help others survive

February 25, 2019Students and parents know college is expensive, but even for those who closely study the bills it can be an uphill battle to find out why.

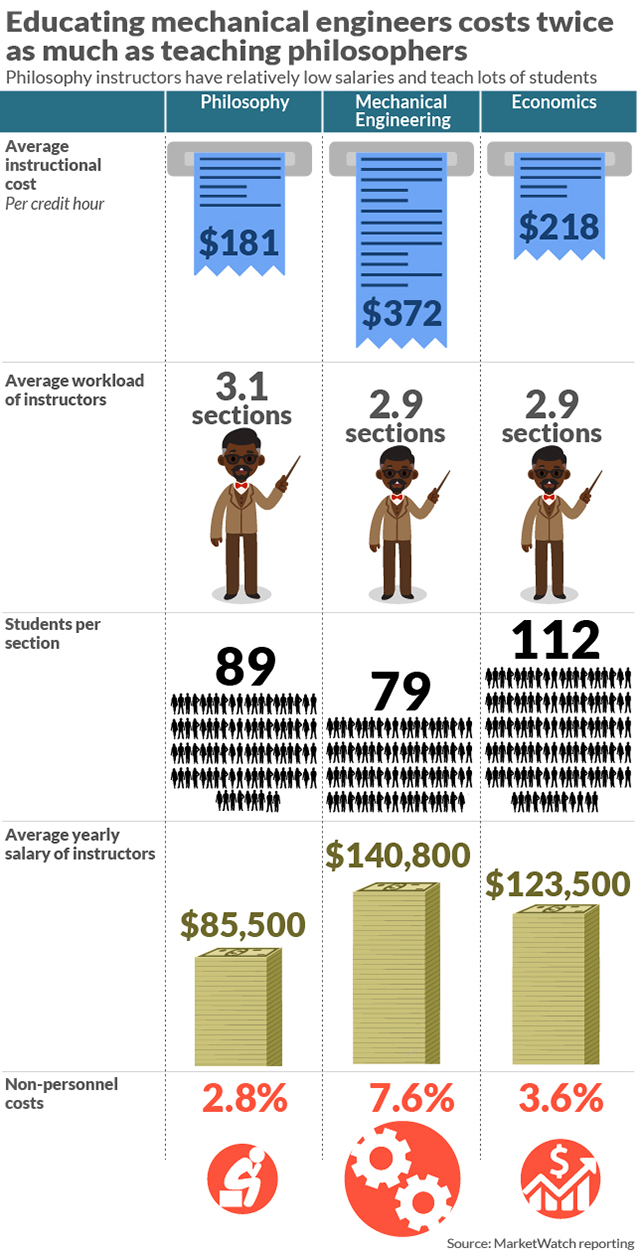

A recent working paper from professors at the University of Michigan, University of Delaware and University of North Carolina examined the different factors that can influence the cost of a college education. The research looked at the cost to colleges of teaching different subjects and how various elements — such as professor salaries or average class size — pull these costs up or down.

What they found: There’s a roughly $300 gap between the most expensive subject — electrical engineering at $434 — and the least expensive — math at $163 — in the cost for each credit a student earns. For comparison, English costs the college approximately $199 for each credit a student earns.

Rising costs have made it nearly impossible for students to afford a college education without student debt.

The findings help bring transparency to the mysterious world of college cost and price. Rising costs have made it nearly impossible for students and families to afford a college education without some student debt, which now stands at $1.5 trillion. At the same time, colleges are under pressure to deliver more to students and, in the case of public colleges, often with fewer resources.

Of course, the study is only focused on one factor in the college costs complex: instruction. It doesn’t look at other elements that could drive up cost and price, like the cost of building a new facility. Even so, understanding the factors that influence the cost of a course can help students and families be savvier consumers, and help universities and policymakers to invest resources more strategically.

“Providing a college education is super expensive and we don’t know a lot about what drives costs of higher education,” said Kevin Stange, a public-policy professor at Michigan and one of the authors of the study. “We wanted to better understand those issues.”

Terrence Horan/MarketWatch

Terrence Horan/MarketWatchTo do this, the researchers analyzed data on costs at four-year universities between 2000 and 2015 from the Delaware Cost Study, a national database of instructional costs and productivity at colleges. They zeroed in on four categories — instructor salary, average class size, average number of courses taught per instructor and non-instructional costs — and assessed how those factors interact with one another to influence the cost of teaching a credit hour of a given subject.

One example is the factors influencing the cost of teaching economics. Though economics instructors pull in relatively high salaries on average, the subject is still pretty cheap for colleges to offer because the instructors teach so many students.

Terrence Horan/MarketWatch

Terrence Horan/MarketWatchThat gap in cost to deliver different subjects can have major implications for schools, Stange noted, particularly as pressure builds to push more students towards some of the more costly subjects like engineering, computer and information sciences and physics.

It can also impact students who — depending on what they study — are either subsidizing their fellow students or benefiting from those subsidies. In other words, students end up covering the costs of those more expensive classes even when they’re not the ones taking them.

‘It’s important that students can easily attain majors which are more expensive.’

Alex McClintic, a senior economics major at the University of Oklahoma, said he hadn’t thought much about how what students study affects the amount they cost the school — and he likes it that way. Students studying English, engineering and history all bring different skills and knowledge to campus and the world beyond college, he said.

Students shouldn’t be dissuaded from pursuing a certain major because of the cost, he added. (His school does charge program fees for certain subjects). “It’s important that students can easily attain majors which are more expensive,” McClintic said.

Courtesy of Alex McClintic

Courtesy of Alex McClinticSome schools charge different tuition based on majors

“We don’t want cost to discourage students,” said Martin Van Der Werf, the associate director of editorial and post-secondary policy at Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce. “Cost can be a signifier of that.”

But over the past 15 to 20 years, college leaders have started to reconsider this philosophy. During the 2015 to 2016 school year, about 60% of four-year public research universities had different tuition policies, up from 6.3% in the 1992 to 1993 school year. That is, student prices are based on the subject or their year in school, according to research by professors at Arizona State University, the University of Louisville and New York University.

Students and parents are increasingly concerned about the return on investment in their college education.

For some students like Omida Shahab, 22, the difference in cost for various subjects just contributes to the overall confusion. Shahab knows that the price she pays to attend St. Louis University is tied in part to the subject she’s studying — a bachelor of science in magnetic resonance imaging or MRI — but she says there’s still a lack of transparency.

“I’ve never understood what they do with that money,” she said.

Students and parents are increasingly concerned about the return on the investment they make in their college education, Van Der Werf said. That means that some subjects, like engineering, may cost more to teach due to equipment, instructor salaries and other factors. But they may also command a higher than average payday for students when they graduate.

“Colleges, in some cases, they have assessed the value of some of their programs and understood that students were willing to pay more for them,” Van Der Werf said. “In the interest of transparency with their customers, universities ought to talk in that kind of language.”

Courtesy of Josephine Martinez

Courtesy of Josephine MartinezA student’s choice of major can be more important than their choice of school

In many cases, the choice of major has a larger impact on a student’s future than their choice of college, Van Der Werf added. As a result, some students feel there’s not much to be gained by paying more to attend a specific school.

Josephine Martinez, 21, understands this concept. In high school, she watched her brother go off to a private university and struggle with debt. That experience “paralyzed” her, Martinez said. She ended up not applying to any colleges.

Ultimately, Martinez enrolled at a community college and began looking at four-year schools to finish her marketing degree. After looking at a variety of schools, including some out of state, she realized, “I was just going to be paying a lot more for a degree that was very equivalent to the degree I was getting here.”

She’s now a junior at the Metropolitan State University of Denver and has yet to pay anything out of pocket for her studies.

Source: Why it costs colleges far more to educate a physicist or teacher than an English major – MarketWatch